MoG changes – what are they good for? We look back on 20 years of what some Whitehall watchers affectionately call “rearranging the deckchairs” to see what’s worked, and what’s been a waste of time and money

Few phrases strike fear into the hearts of civil servants quite as comprehensively as “machinery of government change”. Like earthquakes, departmental reorganisations vary in magnitude and disruption. Some will affect a far-flung bit of the map with little impact on anyone else and no reported casualties. Others condemn cherished empires to the history books and create problems that take years to unravel.

Civil Service World’s two decades of existence have seen scores of MoG changes. Some have drifted quietly under the radar, others not so much.

For those without direct personal experience, it’s easy to forget that institutions like the Ministry of Justice, HM Revenue and Customs, and the Department for Work and Pensions are positively “Generation Z” in government terms. Some departments created in the past 20 years have had lifespans more in line with the average hamster’s.

Chopping and changing the way government delivers is never easy, and effort expended on reorganisation is by definition not directed to other – more fruitful – tasks. The Institute for Government has previously estimated that the upfront cost of setting up a new Whitehall policy department or delivering a mid-sized merger is around £15m. However in a 2019 report it said MoG changes tended to come with a 20% productivity hit from 20% of staff for a period of 10 months, equating to additional costs of up to £34m. Plus, in reality, completing MoG changes can take a lot longer than 10 months.

IfG programme director Tim Durrant says standing the test of time is one sign of a worthy MoG change. Examples include 2001’s creation of the DWP by joining up the Department of Social Security and bits of the then Department for Education and Employment, or 2007’s fashioning of the Ministry of Justice from the Department for Constitutional Affairs and elements of the Home Office portfolio.

Another example is the 2005 formation of HMRC from the merger of Inland Revenue and HM Customs and Excise. It had been a government goal for well over a century. In 2011, CSW reported that then cabinet secretary Gus O’Donnell had a photo of former PM William Gladstone on his wall, accompanied by a quote on the desirability of bringing revenue and customs together. Gladstone died 106 years before it happened – on O’Donnell’s watch as Treasury perm sec.

For Durrant, who was co-author of the IfG’s 2019 paper Creating and Dismantling Government Departments, unsuccessful MoG changes are typically ones that have been poorly thought out or conducted for the “wrong reasons”.

“Obviously prime ministers are politicians; they have political drivers and all the rest of it. And they will want to please their allies and supporters,” he says. “But if you are moving things around because it’s the right thing for pleasing a minister or a faction of your party it’s not really on because of the disruption it causes.”

Durrant considers 2007’s creation of the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills as a prime example. The department was formed from parts of the Department for Trade and Industry and the DfEE – and launched at the time the education department was rebranded the Department for Children, Schools and Families. The rump of DTI was rebranded as the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform.

According to the IfG, a prime motivator for DIUS’ existence was then-PM Gordon Brown’s desire to get John Denham back into the cabinet – without having to remove other cabinet members from their roles.

However, DIUS and BERR didn’t even make it to the end of Brown’s premiership as they were largely recombined as the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills in June 2009. “He realised it didn’t work, which I think is illustrative,” Durrant says of Brown.

Dave Penman, general secretary of civil service leaders’ union the FDA, said the existence of DIUS was so brief that it was disbanded before work to align the terms, conditions, and pay of its newly-united staff had been completed.

“DIUS felt like the absolute worst. The longevity of it, the rationale for why it was done. When it was undone, it wasn’t undone well” Dave Penman, FDA

“That felt like the absolute worst,” he says. “The longevity of it, the rationale for why it was done. When it was undone, it wasn’t undone well.”

According to Penman, HR tangles from the creation and break-up of DIUS “took years to resolve” because the global financial crisis meant no new money was available to rebalance inequalities between newly-thrust-together staff. This is one of the recurring themes of MoG changes. “Treasury essentially said: ‘We’re not giving you extra money for this.’ So it was almost impossible to resolve it in the short term,” Penman says. “Then there was austerity. You had departments literally given no mechanism with which to try and resolve these issues.”

Few MoG changes took place during the coalition government years, with then-Cabinet Office minister Francis Maude wary of their benefit. Much was to change in the wake of the UK’s 2016 decision to leave the European Union, however, which forced David Cameron to resign as PM and saw Theresa May installed in No.10.

May quickly announced the creation of the Department for International Trade and the Department for Exiting the European Union in response to the pressing tasks of delivering Brexit. Meanwhile, the Department for Energy and Climate Change and BIS were merged to create the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Constructing BEIS was seen as necessary to comply with the requirements of the Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975, which dictates that there can only be 21 secretaries of state at any given time. Setting up two new departments, each with a secretary of state, meant one existing department would have to go – and DECC was “it”.

DExEU had been one of May’s Conservative Party leadership commitments. But the IfG’s Durrant says the move was a failure on multiple levels, principally because in the summer of 2016 the then-PM failed to understand how all-encompassing delivering Brexit would be.

“Anything that affects everything in government needs to be run from the centre – it needs to be run from No.10 and the Cabinet Office,” he says. “Carving Brexit out and trying to put it to one side was part of the problem why Brexit became so complicated.

“DExEU didn’t work on a political level, but it also didn’t work on an official level. A lot of departments were like, ‘Who are these upstart people telling us what to look into? We know our areas’” Tim Durrant, IfG

“[DExEU] didn’t work on a political level, but it also didn’t work on an official level. Because a lot of departments were like, ‘Who are these upstart people telling us what to look into? We know our areas’. Whitehall is used to being corralled by the Cabinet Office and by the Treasury to a certain extent. But having a line department trying to manage across all other departments is a very difficult way of setting things up. It’s not the normal way.”

Durrant acknowledges that May was in a uniquely difficult position, and that any PM would have struggled to deliver a good structural solution for Whitehall to deliver Brexit. “Hopefully, the lesson from that is that if there is something that is big and affects all of government, you need to run it from the centre,” he says.

Similarly, DIT had an initial crisis of purpose because for its early months May’s government had not made a decision about whether the UK would leave the EU customs union as part of Brexit. As the IfG observed in 2019, the situation made it impossible for DIT to progress new trade deals until a call was made on the UK’s future trading status.

DExEU was dissolved on 31 January 2020. DIT survived until February 2023, when it was absorbed into the new Department for Business and Trade.

Boris Johnson’s 2020 decision to merge the Foreign and Commonwealth Office with the Department for International Development is perhaps the most classically controversial MoG change of recent years. Ostensibly, it was designed to better align the UK’s aid spending with the nation’s other overseas priorities, particularly in light of Brexit. Some viewed it as a cash grab for DfID’s £10bn budget by a former foreign secretary who had been forced to operate on a fraction of that sum when he was the boss at King Charles Street.

Unpopular with staff from the international-development side – who were massively outnumbered by their FCO counterparts – the merger took more than two years to complete and coincided with a spike in staff turnover.

According to the National Audit Office, the process cost at least £24.7m to deliver, excluding indirect costs such as disruption, diverted effort and the impact on morale. The figure also does not include the department’s new HR and finance system, or its Aid Management Platform programme. Significant IT issues persisted for staff, which is not uncommon for MoG changes. In the case of the FCO and DfID merger those problems also hampered the UK’s response to the fall of Kabul and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Other problems included friction caused by former DfID officials getting different overseas allowances to their former FCO colleagues and a requirement for former DfID staff to have higher-level security clearance than was previously the case. Some former DfID staff did not meet the “reserved” nationality requirements of the FCO and FCDO, barring them from applying for some roles in the new organisation. The requirements stipulate that only UK nationals – or in certain circumstances citizens of the Irish Republic or the Commonwealth – can be employed to undertake particular roles, because of the sensitive nature of the work. Jobs in the Security Service, the Secret Intelligence Service, and the Government Communications Headquarters are automatically “reserved” to UK nationals.

Twelve months after the merger, a survey of senior officials conducted for the FDA union found that just 7.5% considered the reorganisation to have been a success. A March 2024 NAO report on the merger said the new department had experienced higher staff turnover in the years following the merger compared to that of FCO. DfID already had a high turnover rate – of approximately 11% in 2019-20, before the merger was announced.

Turnover appeared to increase the most for middle and higher-grade staff between 2019-20 and 2022-23, according to the NAO. The report said Grade 6 turnover almost doubled from 5.3% to 10.4% over the period, while turnover among senior civil servants increased from 7.6% to 11.7%.

The FDA’s Penman says the exodus was aided by the fact that disaffected DfID officials were not short of options for other jobs. “You can imagine how many NGOs there are in that field, and they’re very well-connected people,” he says. “You can’t necessarily be a diplomat somewhere else, but you can work in the aid sector in lots of places. Part of it was also about the policy outcomes they were trying to achieve.”

The IfG is more sanguine about the creation of FCDO. Senior researcher Jack Worlidge says there is a “strong school of thought” that it made sense to bring development into line with broader foreign policy. “I know lots of Conservatives who are pro aid spending but think the FCDO merger was a good idea,” he says. “Separate to that is the question of how it was done, how disruptive it was and how long it took and, downstream, how the department was then able to react in situations like the Afghanistan withdrawal.”

Durrant notes the Conservative Party has a track record of combining aid with foreign policy but says Johnson’s error was being very critical of DfID when the merger was announced. “Civil servants obviously serve the government of the day, but they are also human beings and it put people’s backs up,” he says. “The aid sector, which is a big, important, lobby, were very anti it and it was very much informed by Johnson’s time as foreign secretary. There was a sense that this was someone who had been foreign secretary and had been jealous of DfID.”

The most recent large-scale MoG change has been the creation of the DBT, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology – all established in February 2023.

The move essentially scrapped DIT and BEIS, and created standalone energy and technology departments, with some tweaks to the Department for Culture, Media and Sport for good measure. Shortly after last July’s general election, the Starmer government announced that the Government Digital Service, the Central Digital and Data Unit, and the Incubator for AI would all move from the Cabinet Office to DSIT to “unite efforts” on the digitisation of public services in a single department.

The Cabinet Office has a role in advising the prime minister on MoG changes and an ad-hoc team that can be stood up to assist departments with restructuring. For the creation of DBT, DESNZ and DSIT, a cross-government oversight board was set up – with a senior DESNZ official at its helm. A new integrated corporate services function was also launched for DESNZ and DSIT. It handles estates, security and digital services and some of the departments’ commercial, finance and HR needs.

Commentators told CSW that the approach taken with the creation of DBT, DESNZ and DSIT appeared to have more central-government support than had been the case with other recent MoG changes. The Cabinet Office declined the opportunity to talk about the evolution of its MoG-support work for this feature.

Worlidge is relatively supportive of the 2023 MoG changes. “BEIS was large, unfocused and had a huge number of remits and spanned a massive range of policy,” he says. “So to reunite the bits of DECC which previously existed with the other stuff in DESNZ makes a lot of sense. And having DBT, as it is now, bringing trade and business back together makes more sense. There’s something about splitting up big and complicated departments as well when they have been smashed together by previous governments.”

He acknowledges DSIT was “very much a reflection” of then-PM Rishi Sunak’s personal priorities and assumptions – raising questions about its future. Nevertheless, the Starmer government’s decision to proceed with adding the GDS, CDDU and i.AI to the department looks like a vote of confidence.

Worlidge and Durrant are of the opinion that the fewer MoG changes civil servants are subjected to, the better. “It’s so disruptive to the work of a department if you’re talking about big restructures or demergers,” Durrant says. He argues that other approaches to breaking down silos and cutting down departmental boundaries should be tried first – with the Starmer “mission boards” approach being one way of doing that.

Nevertheless, there is one exception from the IfG: earlier this year its Commission on the Centre of Government called for No.10 and the Cabinet Office to be restructured into a new Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, along with a separate Department for the Civil Service.

Penman points to HMRC as an example of a merger that had “strong rationale for it”, with lots of overlapping areas of work and potential for intelligence-sharing and joint skills development.

Despite the existence of clear cultures remaining from its predecessor departments after almost two decades, he says the MoG change that created HMRC has been “one of the successful ones”.

“There are always legacies in any organisation, particularly when you had two organisations with such strong identities and history,” he says. “But it makes sense, and if it makes sense, it’s worth the pain. It drives innovations, it makes policy outcomes easier.”

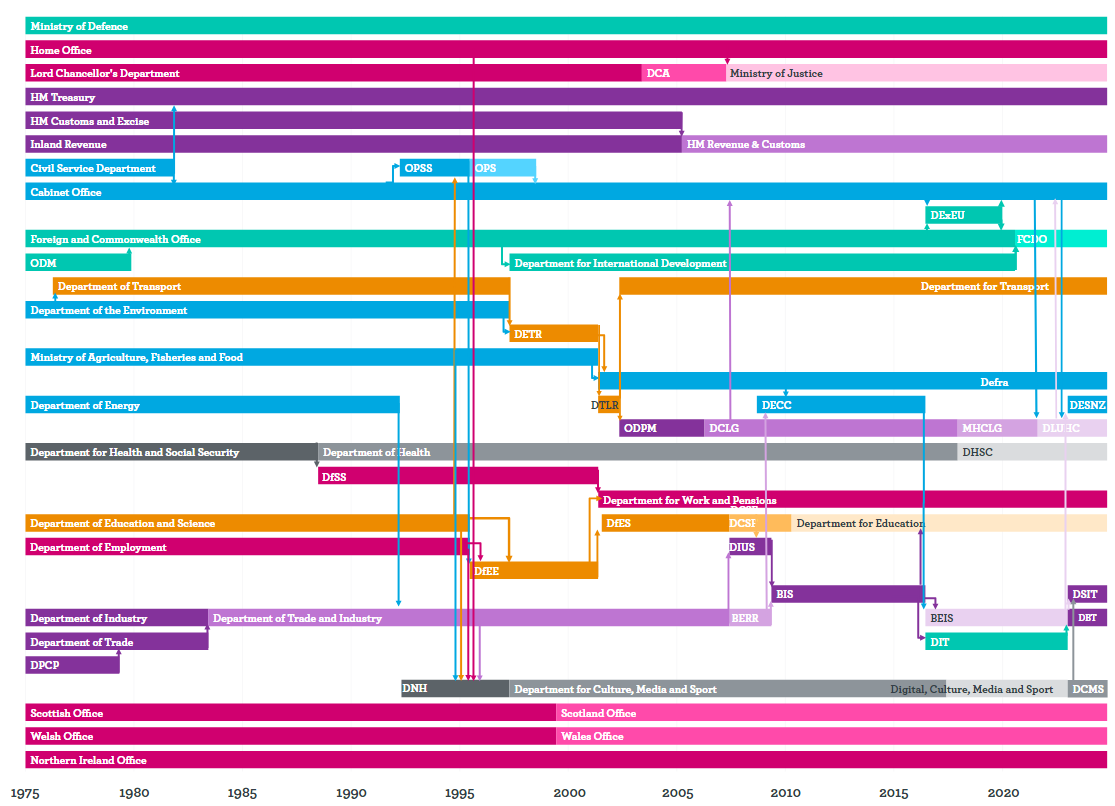

History of departmental reorganisations, 1975 to February 2024

Source: Institute for Government analysis of data from House of Commons, and Butler and Butler, British Political Facts, 1986. Copyright IfG

Source: Institute for Government analysis of data from House of Commons, and Butler and Butler, British Political Facts, 1986. Copyright IfG