You really don’t need me to tell you that our public services face grand societal, economic and technological challenges, from an ageing population and climate change to stagnating economies across the global north.

The UN projects a global shortage of 18 million healthcare workers by 2030. Meanwhile, healthy life expectancy is falling in many developed nations – we can expect to live longer than previous generations, but we are going to get sicker earlier and die more expensively than ever.

Not an entirely uplifting or even morally sound sentiment, but it is against this backdrop that innovation within our public services isn’t just desirable. It’s vital.

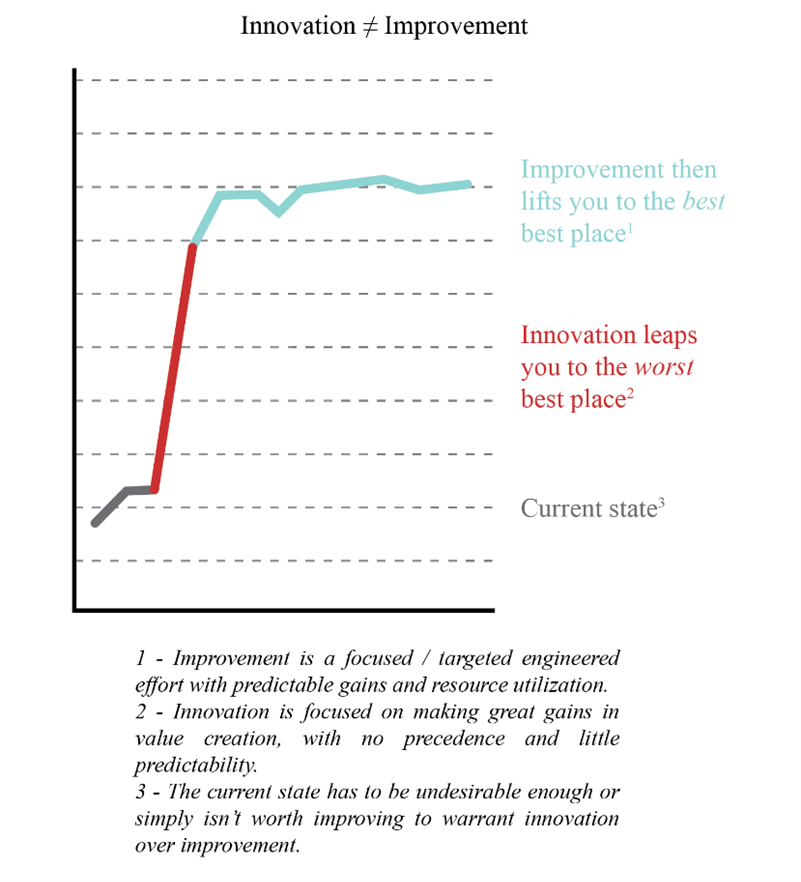

What does innovation in public services look like? You’d be forgiven for leaping straight to “invention”, which is an innovation synonym for most people. Yet time and again, the bigger prize is to create new value through the adoption of proven innovation. That might be about lifting and shifting from another part of your sector, or adapting some process, practice or capability from an entirely different one.

Building innovation capability

Research shows that public sector organisations often struggle with innovation due to risk aversion and entrenched cultures. In the health sector, for example, the Health Foundation’s Spread Challenge paper highlights that even when beneficial innovations exist, scaling them across the NHS proves difficult, if not impossible. However, there are several practical steps organisations can take to build their innovation capability.

“It’s almost impossible to gain senior buy-in without robust evidence that something has worked elsewhere. Innovation requires faith, but not blind faith”

Establish a clear innovation cycle

Organisations need structured approaches incorporating problem clarification, opportunity scouting, experimentation and evaluation.

Create safe spaces for testing

Living labs, like those operated by the Catapult Network, provide controlled environments for trialling new approaches without risking core service delivery, allowing innovations to be tested in representative settings before wider deployment.

Build cross-sector partnerships

Some of the most impactful innovations emerge when sectors collide. Collaboration between the UK Space Agency and the NHS through the “future hospitals initiative” is now being expanded in recognition that seemingly unrelated sectors can offer value to one another.

Focus on evaluation

Without robust evaluation of benefits, innovations struggle to spread. It’s almost impossible to gain senior buy-in without robust evidence that something has worked elsewhere. Innovation requires faith, but not blind faith.

Having a go

The reality for many of us is that building innovation capability must happen within existing structures and resources. To get this started, aim to identify colleagues who exhibit innovative behaviours. Look for those who are naturally disruptive but constructive; action-oriented “doers”; empathetic “feelers” who understand user needs; and detail-oriented professionals who can ground ideas in reality. These diverse perspectives are crucial for successful innovation teams, and can get you on the way without ripping up your organisational design to bring these skills into the fold.

Consider how your organisation deploys its strategy. Is there space for innovation to be part of the delivery mechanism? Can you secure some modest fiscal resource? Even small innovation budgets can be leveraged effectively by using them to attract external investment and forge partnerships. The key is to start somewhere, learn fast, and build momentum through early wins that demonstrate the value of innovative approaches.

The benefits of innovation

When done well, public sector innovation can deliver remarkable results. The “Wigan Deal” – as described in Hilary Cottam’s book Radical Help – demonstrates how innovative approaches to public services can improve outcomes while reducing costs.

In healthcare, the Buurtzorg model of community nursing showcases how innovative organisational structures (flatter, in this case) can both empower staff and improve patient care. Behavioural science has driven down bullying in schools through the “Roots” project in the US – now being trialled in the UK – and Alaska’s permanent fund dividend has fostered civic ownership over natural resources. None of these are perfect examples; there are moral arguments applicable to them all, but the benefits are worth considering before you make up your mind.

Looking ahead

Thomas Davin, director of innovation at Unicef, says the changes needed to address today’s challenges must be radical, not incremental. Public sector organisations that develop their innovation capability now will be better positioned to meet future challenges effectively.

While innovation isn’t easy, the alternative of continuing with business as usual is no longer viable. We need public sector organisations to be capable of both adopting proven innovations and developing new solutions to emerging challenges. This requires building innovation capability at all levels.

There’s also something to be said for channelling Simon Sinek and working out “why”. OK, we’re not marketing computers, as Sinek famously articulates in his Ted Talk and book Start with Why. But knowing the core purpose of why we are seeking to innovate our public services helps with the last and most essential characteristic of successful innovation: consistency of purpose.

It is on us, and no one else, to bring about a better future for public services. Could there be anything more exciting? I hope the message is clear. Innovation in public services isn’t dead, but if it is to thrive, it needs a good jolt from the defibrillator.

Tony Mears is deputy director for strategy at Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust and a former civil servant. His book, Innovation is Dead: Dispatches from the Front, is published on 21 April and available to pre-order