Whether you know it or not, you’ve likely encountered a Private Finance Initiative (PFI) or two. Have you ever wondered how some public projects, such as hospitals, schools, prisons, and even roads, are funded and built? Chances are it’s through a PFI.

What is a PFI?

PFIs are long-term agreements between a private party and a government entity. The private party designs, builds, finances, and operates the government entity's asset – whether for an NHS Trust, Local Authority, or a central government Ministry/Agency. This agreement style is often compared to a mortgage, where funds are taken from another party to pay back over time in exchange for a building and often a managed service within the building (catering, FM, cleaning, etc.), typically for 25-30 years.

A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), a company specifically created to implement the PFI project, has no other business than running the PFI. It creates subcontracts to undertake the project, using finance from lenders and investors, typically through debt and equity.

Establishing an SPV as a separate legal entity isolates the parent companies from financial risks related to the PFI project. Furthermore, the SPV is responsible for overseeing the construction of the asset, maintaining and operating the asset over the contract term, managing the contract, and collecting payment from the public sector client over the contract term.

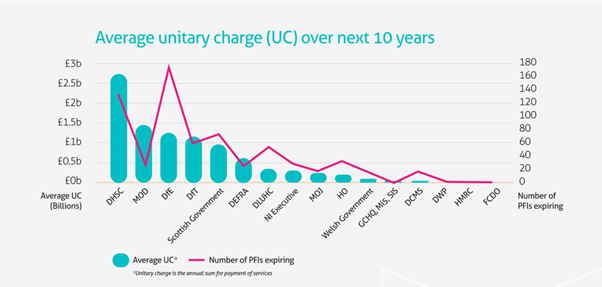

PFIs have played a significant role in British infrastructure development since being introduced under a Conservative government in 1992. Expanded under Tony Blair’s Labour government from 1997 (and those that followed), today there are 669 live PFI contracts, with a total capital value of over £50bn, delivering significant requirements across the public sector – particularly in Health, Defence, and Education.

*Unitary charge is the annual sum for payment of services

*Unitary charge is the annual sum for payment of services

Over the years, the public and the press have criticised PFIs. They were positioned as poor value for taxpayers' money, with infamous accounts of reckless overspending – a £5,500 sink here, a £884 chair there – but the benefits were seldom highlighted.

PFIs tend to be contracted on an asset being built and used and then handed back to the public sector entity at a stated time and in a certain condition. When a PFI asset (e.g., building, etc.) is handed back at the end of the contract, the ownership of the budget and the ability to reallocate funds return to the Authority finance team.

This works well if the contract is effectively managed and the organisations behind the SPV remain enthused, focused, and in business. The collapse of Carillion in 2018 brought to light significant issues with how the contracts were managed. Financial strain in the form of cost overruns and delays that led to the collapse also saw the risk transfer revert to the public sector, questioning the effectiveness of risk transfer in PFI contracts. That same year, the government ended PFI for future infrastructure projects. Under a new government, the public must wait and see if PFIs will be left in the past or reintroduced as part of the solution to public sector budget constraints – whether under the guise we’re familiar with or otherwise.

The history of PFIs also provides some key learnings and considerations for the future: What if the contracts were better managed moving forward? What value can be saved from the hundreds of contracts set to expire between now and 2053? If contract management has been under-utilised, how much value has been lost yet could be recovered?

Challenges and barriers, or a cost opportunity?

Contract Management in relation to PFIs has been generally inconsistent (as found by a National Audit Office report). Many thought of PFIs as a ‘fire and forget’ solution that would self-manage, but in reality, they are active complex contracts, albeit over a longer period than usual. The need to contract to manage these agreements is more important than ever, as ‘scope creep,’ ‘over-enhanced service delivery,’ and lack of challenge means that SPVs may have been significantly overpaid for decades.

Effective in-life contract management should enable alignment with contract commitments and thus not leak value. Without that, an intervention or periodic reviews should offer the chance to recoup value. Examples of these PFI contract management ‘health checks’ are provided below.

The planned replacement of an MRI Scanner, which was costed into the Hospital PFI, was due, but the existing machine was fully effective and did not need renewal. Maintaining the existing scanner and removing the additional cost of the new scanner delivered ongoing financial efficiencies.

PFI companies on two estates were catering for a theoretical maximum number of staff on each site. The PFI charged the total amount (mainly for cleaning and catering)—in one case, for 1,200 meals per day when only c.200 were taken. Challenging this resulted in the lower ‘actual’ rates being charged, with a sliding scale introduced to allow for any surge in numbers. This reduced the ongoing costs and allowed an opportunity to recover from the historical overpayments.

Approaching expiry, contract management provision on an accommodation PFI demonstrated that maintenance charges continued to be paid, yet actual maintenance of properties had effectively stopped two years before expiry. This would have resulted in significant spending after the contract ended to return assets to an acceptable and safe condition.

Government guidance suggests starting a contract expiry process seven years before the expiry date. This should allow sufficient time for planning the follow-on services, including requirements and budget setting, in-house training for managing such services, and retendering of what could potentially be numerous contracts as the services from the PFI separate and become authority-owned.

The resource burden to manage this and do it well and cost-effectively is significant across the public sector. Mistakes, delays, or under-estimating efforts could cost millions of pounds due to possible extension agreements and missed opportunities to engage with the industry effectively. Further, with c.30% of live PFIs set to expire by 2030, there is a risk that the sector will face a skills shortage in the market to address these, and the resources needed are unlikely to all be available in-house. Yet, the perceived high cost to manage may be far outweighed by the substantial cost of failure.

What’s the value?

World Commerce & Contracting (WCC) reports that the latest average pre-contract value leakage is 8.6%—the worst performers see this rise to as much as 20%. Moreover, without adequate management, research suggests contracts can lose up to 40% of their value over the in-life period.

Now consider the complexity and length of a PFI contract and the effect mismanagement could have on the value realised.

So, how do you create value from PFIs?

There are two main ways to create value: first, through in-flight PFI contract management to recalibrate ongoing/changing requirements, avoid unnecessary investment, and manage the service delivered. Second, through effective management of the PFI expiry process. When done well, the former can fund the latter. In our latest report, we explore how this is achieved.