According to government data, there are over 700 Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs), and the majority will expire in 2025. Why should this be big news? Quite simply, because we are talking big numbers, critical services and a complex challenge emerging.

A National Audit Office report in 2020 revealed the capital value of the estimated 700 PFI was around £57bn. Further, the report highlighted that four out of nine surveyed authorities, who had already taken back ownership of the PFI assets at expiry, were not satisfied with the asset’s condition. Big news, indeed.

PFIs are long-term contracts where the private sector designs, builds, finances and operates an infrastructure project for the public sector. First introduced in the ’90s, the scope of assets delivered by PFIs includes hospitals, prisons, roads, defence, housing, and schools. These are huge projects supporting crucial infrastructure and critical services. For example, at the MoD, the Defence Aquatrine contract is vital for managing all water services for defence, including wastewater treatment and drinking water distribution.

PFIs are complex long-term arrangements, allowing for early-stage investment and profit earnings later. The infrastructure and services they provide are embedded into the fabric of how we live and work, but the contracts come with an expiration.

With many PFIs set to expire, organisations face the daunting task of bringing the PFI back in and needing to develop a complex transition and exit plan (often involving an extended supply chain or multiple partners) – whilst ensuring continuity of service throughout the handover process.

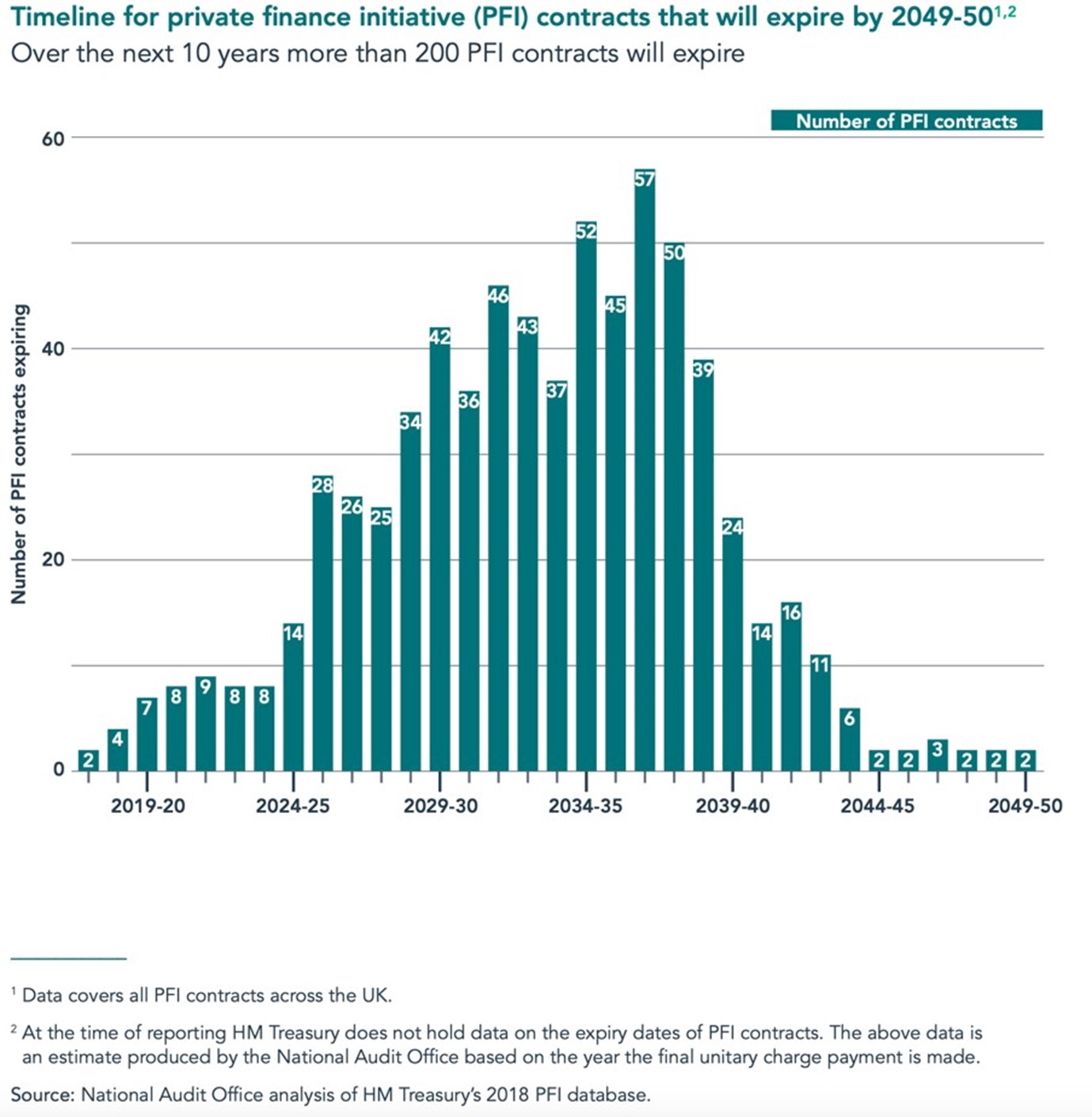

Although many PFI expiries are imminent, the peak is between 2025 and 2038 (see chart below).

The Department for Education and the Department of Health and Social Care have the largest volume of PFIs, with schools and hospitals accounting for most projects. In terms of PFI by value (based on the outstanding Unitary Charges that are outstanding), the MoD is second behind the DHSC.

What does this mean for the public sector management team?

Commercial teams are faced with two critical challenges: visibility, and capability.

Firstly, as highlighted by the NAO report, commercial teams may lack insights into the condition of an asset and the roles and obligations of parties at expiration. This can be further compounded by the possibility that documentation may have been handled in hard copy when the PFI was let. Therefore, the digital tools and data records are not compatible with what has been developed.

Secondly, with many government departments and authorities already “running hot” on resources, commercial teams may struggle to resource sufficient capability to tackle these complex projects, which might be a “one in a lifetime” for many commercial professionals.

The surge of activity required is going to include activities like supporting early health checks, making or buying decisions, analysing the contracts in the current PFI supply chain, conducting due diligence on the assets and their associated maintenance regimes, sourcing expiring contracts, on-boarding and managing contracts that run beyond the PFI expiry.

What should commercial teams be doing?

Firstly – start planning early! The IPA recommends that “preparation should start seven years before expiry, or earlier for more complex projects”. Whilst this may not be possible for all departments, the reality is that replacement contracts for PFI services may require an 18–24-month process to allow a compliant process and an orderly onboarding transition for the new supplier.

There are also a number of critical activities that will require focus, internal resources, and potentially specialist external support:

- Ensuring that the quality of data provided by the PFI provider is in line with their contractual obligations.

- Subject to the above, look at alternate arrangements and providers to make practical plans and execute the handover. This includes an assessment of the contract ecosystem supporting the PFI, as there are likely to be a number of supporting contractual arrangements.

- Develop a delivery model and procurement strategy for the post-PFI services, which requires an assessment of internal and external delivery capability.

- Scope and procure the services required to support the transition, complying with the public contract regulations – it is likely that this will entail the appointment of legal specialists or property advisors.

- Scope and procure the services required post-transition, which may be for services outside the scope of the original PFI (for example, cloud storage services).

- Scope and deliver a robust transition and exit plan.

- Contract management of on-boarded new contracts.

- Knowledge transfer to the in-house commercial teams (and relevant category teams).

Conclusion

For many procurement teams, PFI handbacks represent some of the most complex transactions in their portfolio, involving business-critical assets, with demanding resource and capability requirements coupled with immovable deadlines.

If they have not done so already, commercial teams should assess their exposure to PFI and commence early-stage planning in line with the key steps above. This includes early socialisation of the challenge and engagement with stakeholders – the existing provider, potential alternate suppliers, and professional advisors to ensure the challenge is tackled early and delivery risk is mitigated.