‘Japanese Pillow Learning’ was the title for a session at a management conference that my friend and mentor Dr Jenny Harrow (later Professor Harrow) and I were attending in the early 1990s. We were, mischievously, intrigued and decided to go along.

As a newly minted academic (I’d started in 1990) I was surprised by what seemed to be a somewhat provocative title. And I was into Japanese culture and had come across books with similar titles.

But the session turned out to be about something entirely different.

It was about teaching Japanese children how to think. And the pillow was merely a teaching device.

Japanese culture is, as anyone who has seriously engaged with it knows, very comfortable with contradictions and paradoxes.

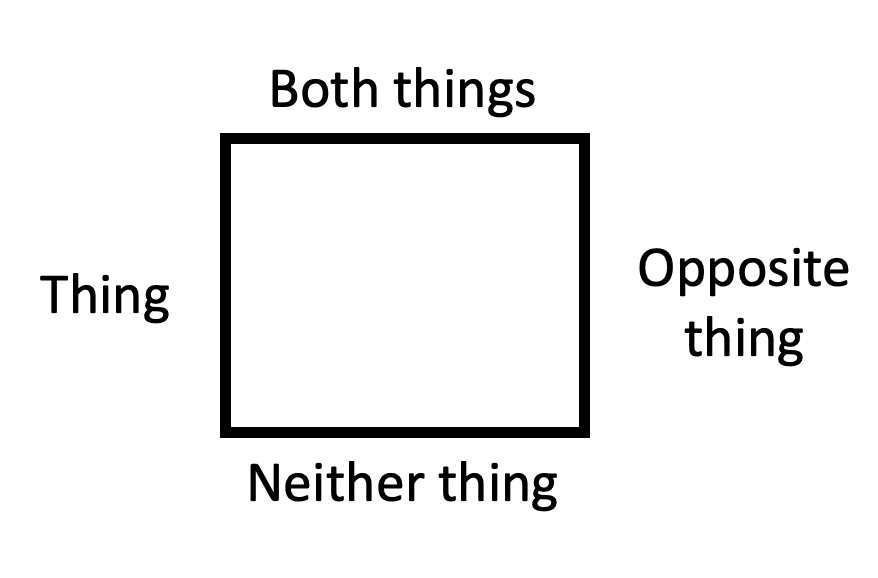

The idea was very simple. The teacher would place a square cushion on the floor. Two opposites sides represent a choice, an either/or dilemma – A or B.

Then pupils are invited to imagine a third side being ‘what if both A and B were true, or present?’: A + B.

Then pupils are invited to imagine a third side being ‘what if both A and B were true, or present?’: A + B.

And also to think about what would it be like if neither thing were true?

By this point you are probably asking yourself – yes, but what has this to do with the civil service? Stay with me.

Back in the 1980s, the Thatcher government thought the Civil Service was too bureaucratic and centralised. Civil service managers didn’t have enough power and autonomy to get on with the job.

They tried several initiatives to try to remedy this perceived problem. These included the Financial Management Initiative (FMI 1982) and later the much more radical Next Steps Program of agencification (1988). And in the early 1990s there followed a programme of devolving powers over pay, grading, recruitment, staffing numbers, etc away from ‘the centre’ to departments and agencies.

At the time I was doing a lot of research on agencies and bits of consulting work with some of them. I was also part of consultancy and research team helping the Cabinet Office with the supposed decentralisation of personnel management process.

The overarching ‘story’ that was being told was of decentralisation and the empowerment of line management to ‘get on with the job’.

But the more I talked to people at the ‘coal face’ they told a very different tale. The picture was much more mixed and confusing – it certainly didn’t feel like the official narrative.

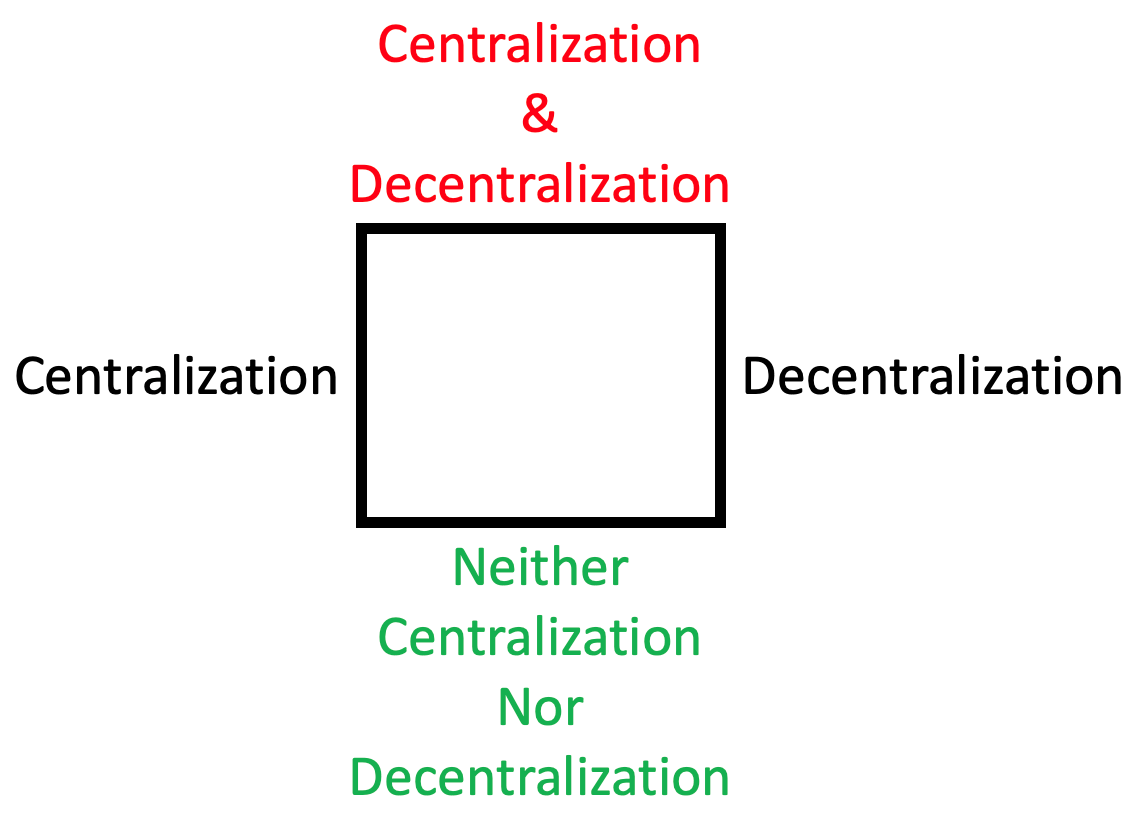

It was then the thought occurred to me: what if what was happening was neither decentralisation nor centralisation but both, at the same time? The third option in Japanese Pillow Learning?

And that was what was happening. In this case it was what I called “strategic centralisation and operational decentralisation”.

And that was what was happening. In this case it was what I called “strategic centralisation and operational decentralisation”.

Traditionally ‘the centre’ in Whitehall had sort to control pay and staffing costs through all sorts of detailed controls. Everything was (supposedly) centrally controlled – originally by the Cabinet Office and latterly in HM Treasury.

But the centralised control system leaked around the edges. So Treasury could control the grading system and what pay was given to each grade. But what departments and agencies could do to get around these controls was what was called ‘grade inflation’. They might not be able to give an individual a pay rise – but they could regrade them upwards instead. So despite supposedly tight centralised controls, HMT found pay bills rising.

The solution they came up with was strategic centralisation of the pay bill, with operational decentralisation of how the pay ‘cake’ could be divided within a department or agency.

Departments and agencies were told how much they could spend in total on wages – how they spent it was (supposedly) up to them. They could change grading structures, employ more less staff, give out performance related pay – as long as they stayed within the pay envelope.

In practice of course the reform process was much more messy than many thought. A survey of human resource managers in departments and agencies that we conducted in 1997 for the Cabinet Office found that many of the centralised micro-management controls had survived the reform process, either formally or informally. Inertia is a powerful force.

And of course there was some informal decentralisation already at work in the supposedly highly centralised pre-reform system - like the ‘grade drift’ problem mentioned above. Reality is rarely simple.

So Japanese Pillow Learning, or what I now call the ‘parabox’, turned out to be a useful thinking tool. Something I still frequently use. Even if it wasn’t what Jenny and I expected.