Public sector productivity always matters – in any country. But with last week’s UK Budget and forthcoming election, it has moved from a geeky side-show issue to centre stage.

For all the noise and fury in parliament this week, there is general agreement that there’s not much more money (from taxes or borrowing), alongside plenty of frustration with the quality of public services. And there’s no shortage of demand in the pipeline with an ageing population and long waiting lists in the health sector. Something has to give. Increasing productivity looks like the only “get out of jail free” card.

Against this background, the chancellor announced the chief secretary to the Treasury-led Public Sector Productivity Plan. It is a serious piece of work, though curiously buried in a long list of supplementary publications under the title Seizing the Opportunity: Delivering Efficiency for the Public. It is also a more muscular play by the Treasury into public service reform, a role historically led by No.10 and the Cabinet Office.

What is public sector productivity and why does it matter?

Public sector productivity essentially refers to how much you get out for what you put in. It sounds simple but it is notoriously difficult to calculate. For example, in health you might ask how many GP consultations and hospital operations you get for the money you are putting in. But consultations and operations are, strictly speaking, ‘outputs’ not ‘outcomes’. A hospital might increase its output by doing more speedy operations, but if the medical results deteriorate as a result of the extra speed, or they start operating on more people who would have been better off without an operation, then true "outcomes" might actually worsen.

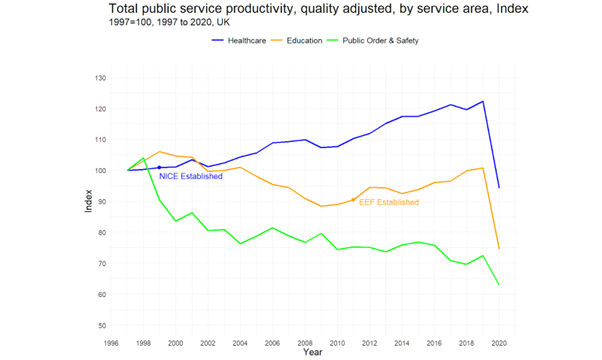

Nonetheless, the Office for National Statistics and others have produced data series that attempt to address these concerns, albeit classing these data as "experimental". The top level, or amalgamated summary of these data, show a modest increase (really very modest) in UK public sector productivity – mentioned by the chancellor in his speech. But digging a little deeper shows a striking contrast between different parts of the public sector.

Explaining the difference

Health service productivity rose through Labour and Conservative governments until it collapsed around the time of the pandemic – it is yet to recover. Education productivity meanwhile fell through the Labour years (though note spending goes up, and performance does improve) but then goes up after 2010. Home affairs and criminal justice shows steady falls in productivity across both Labour and Conservative governments.

A key difference between these three domains is the extent to which they are populated by evidence-based professions, and backed and driven by evidence-based institutions.

Health is, and remains, by far the most overtly evidence-based public service. It may not be perfect but the day-to-day practice of medicine is a seriously evidence-based activity. Billions are spent on developing and testing the efficacy of drugs. Doctors regularly read and contribute to medical journals and they have robust training and testing that keeps them up to date. They also have the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), set up in 1999, that systematically trawls and summarises the evidence. It's not ministers but medical experts that drive the recommendations on “what works”.

"Education is arguably the closest example we have of a “zero-to-hero” of public sector productivity turnaround"

At the other end of the spectrum, domains like criminal justice have long been dominated by political and public considerations. Research budgets to find more effective ways of reducing crime or increasing public safety are orders of magnitude less than medicine. Police officers, judges, and lawyers – for all their talents and efforts – aren’t in the routine habit of running experiments, and it’s not obvious what their equivalent of the BMJ is. It is very welcome that there is now a Society for Evidence Based Policing. Yet while medicine is littered with dozens of highly funded and prestigious academies, SEBP is unsupported by the government – and has only just managed to take on its first employee.

Education is a fascinating contrast between the two. It is arguably the closest example we have of a “zero-to-hero” of public sector productivity turnaround, and probably the stand-out example of the UK moving up the international rankings in public sector performance. Did something change in the wake of 2010? One key innovation is that the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), the What Works Centre for education, was created. It set about trawling through the evidence about what works, as well as organising and funding hundreds of large scale RCTs, involving millions of children and thousands of schools. The majority of schools in turn now use the EEF toolkits and guidance to shape what they do. And there’s been the creation of an education profession – not just unions – along the lines of a medical academy.

Productivity requires painstaking intervention but it can be done

Public sector productivity really matters, and especially now. It’s not an easy path or fixable with a few quick announcements in Westminster. It’s about taking apart the thousands of choices and decisions made by public sector professionals every day, and carefully testing which interventions and areas of spend work a little better than others, and then painstakingly implementing and adopting those changes.

But it can be done. We live longer today than our parents and grandparents, not because of good intentions but because of the slog and effort – from Archie Cochrane forward – to make medicine an empirical enterprise. There is no reason why we can’t do this more generally. Indeed, whatever government the UK has at the end of 2024, the year that 60% of the world goes to vote, it’s probably the best single play we’ve got to have better public services at a tax level the public support.

David Halpern is president and founding director of the Behavioural Insights Team. He was the first research director of the Institute for Government and between 2001 and 2007 was the chief analyst at the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit