The darkest days of the second world war were an existential threat to the United Kingdom and ushered in a new era of powerful campaigns aimed at maintaining the nation’s spirit and countering attacks from Germany.

The Ministry of Information, which was based at the University of London’s Senate House building, produced a huge range of posters designed to shape behaviour and motivate the public. In the 21st century, the “Keep Calm and Carry On” poster is the best-known example. But although it has become ubiquitous on mugs and tea towels, it was never publicly released.

Posters that did achieve fame in their day encouraged citizens to “Dig for victory” by growing their own vegetables; spend money wisely by shunning the “Squander Bug” – a cartoon creation helpfully emblazoned with swastikas for ease of identification; and “Make do and mend”. They also spread important messages designed to protect state security.

Some of the communications prowess that was honed between 1939 and 1945 filtered through to peacetime uses in the aftermath of the conflict.

The Central Office of Information was established in 1946, when the Ministry of Information was wound up and individual departments resumed responsibility for information policy.

Its aim was to support central government departments and public sector bodies to secure policy objectives through value-for-money communications. The COI was closed down by the coalition government in 2011 in the early months of its austerity drive. Its functions were transferred to the Cabinet Office.

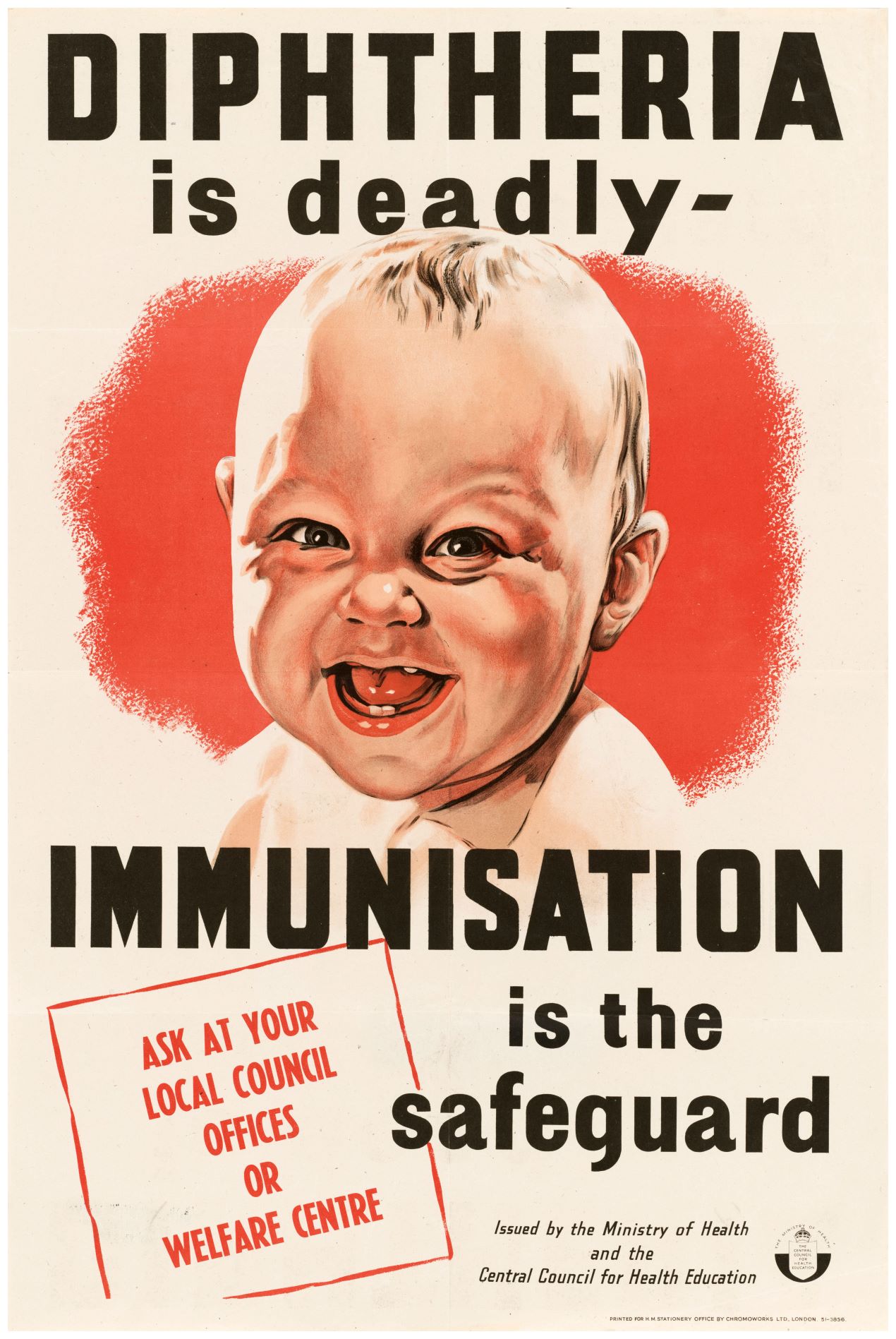

In 1940 – eight years before the launch of the National Health Service – parents were offered the opportunity to have their children vaccinated against diphtheria for free, resulting in a 50-fold reduction in cases over the next decade, according to Gareth Millward, author of Vaccinating Britain: Mass Vaccination and the Public Since the Second World War. After a successful first decade, the Ministry of Health began to fear that public apathy about vaccination might lead to a return of the deadly bacterial infection. So a publicity campaign promoting immunisation was maintained throughout the 1950s.

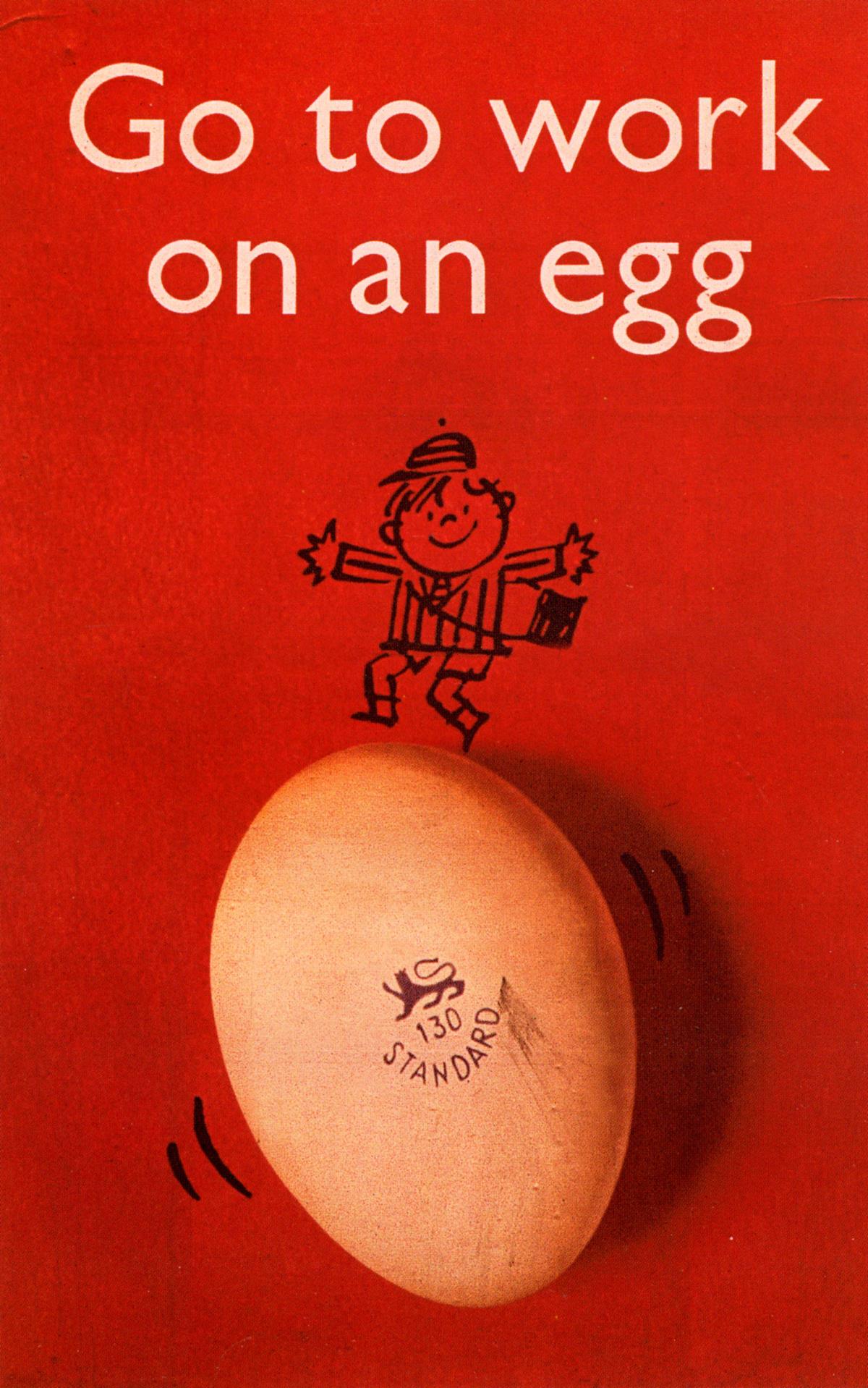

Of all the things you could use your comms prowess to influence, you might think encouraging the British public to eat eggs for their first meal of the day would be low down the list. Particularly at a time when there was a distinct lack of supermarkets with whole aisles dedicated to alternative breakfast treats. Nevertheless, the British Egg Marketing Board’s “Go to work on an egg” campaign – which author Fay Weldon had a hand in – found its way into the nation’s hearts and stomachs.

The British Egg Marketing Board was created by the government in 1956 to stabilise the market for eggs after a collapse in sales, continuing its work until 1971. The poster above dates from 1957.

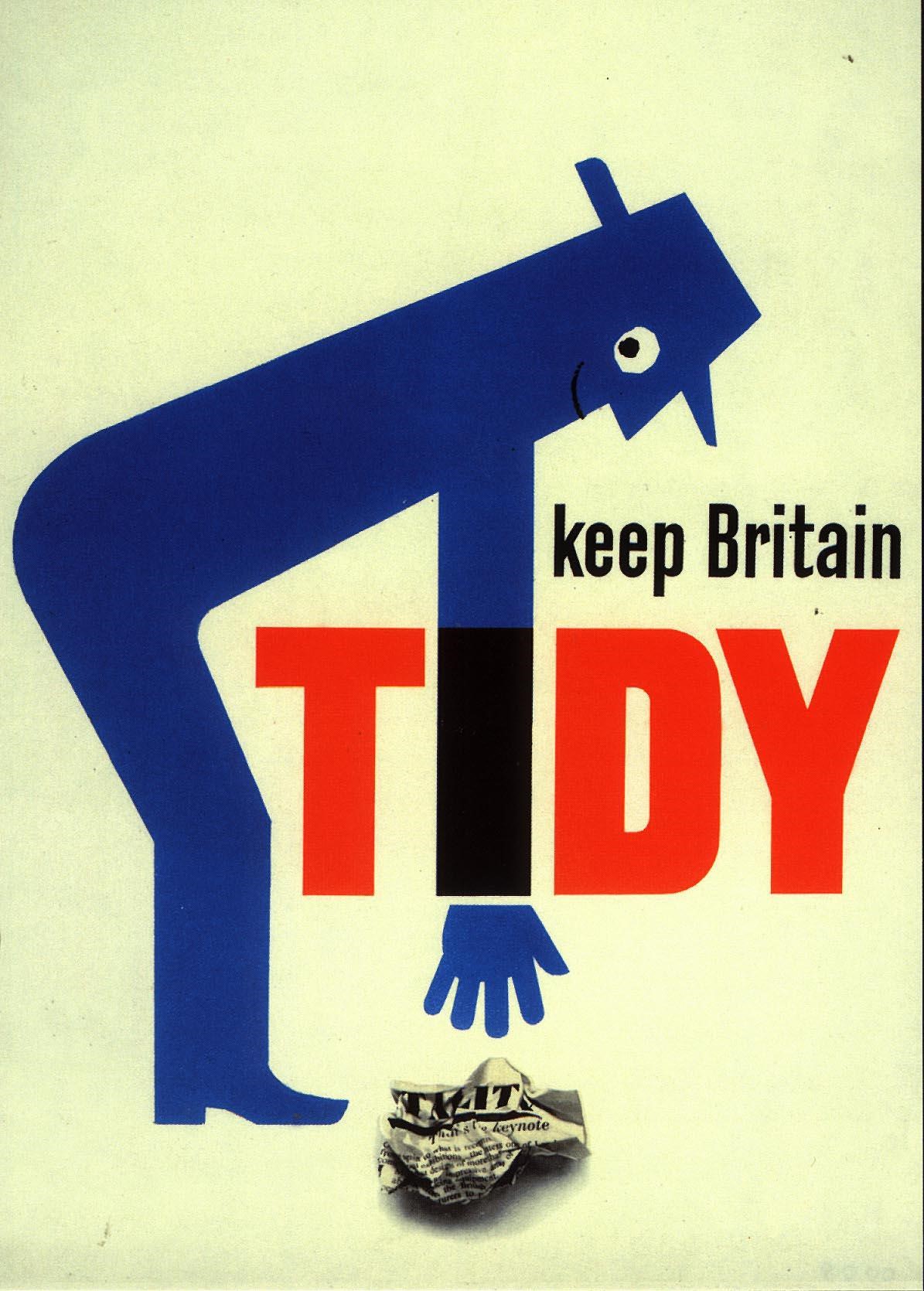

While the charity campaign Keep Britain Tidy grew out of a resolution passed by the National Federation of Women’s Institutes in the 1950s, some of the more iconic posters produced bearing the name of the cause were the work of the COI. History does not record what alternative slogans were considered, but contenders must have included “Oi, put that in the bin!” and “Do you want to live in a tip?”.

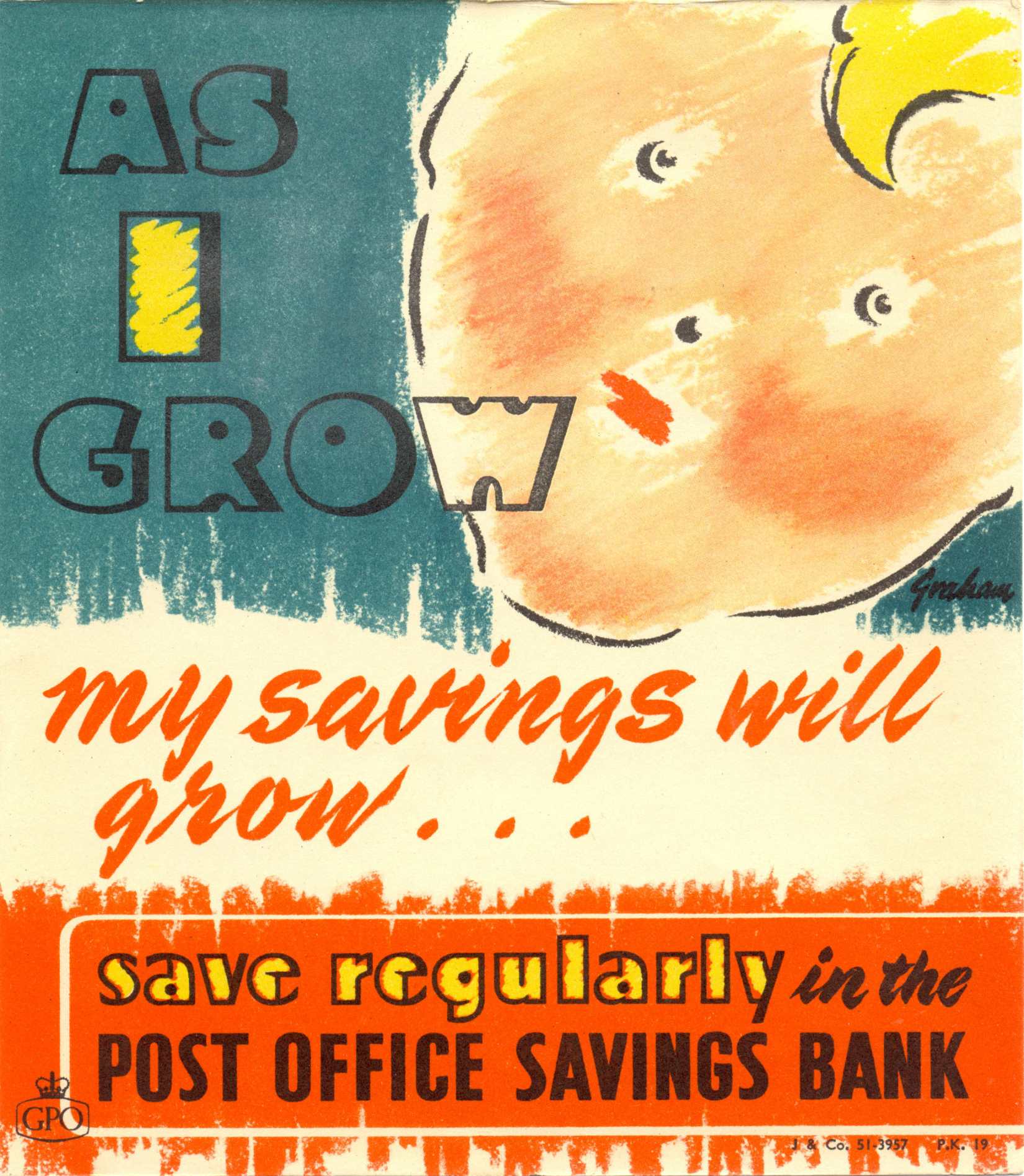

In simpler times, when the state hadn’t been required to bail out high-rolling financial institutions who got their sums wrong – or create trust funds for all children, the General Post Office encouraged parents to save for their kids’ future, among other things. The Post Office Savings Bank became the National Savings Bank in the late 1960s. It is now part of National Savings and Investments. These days, Bank of Ireland provides most savings accounts available through the Post Office.

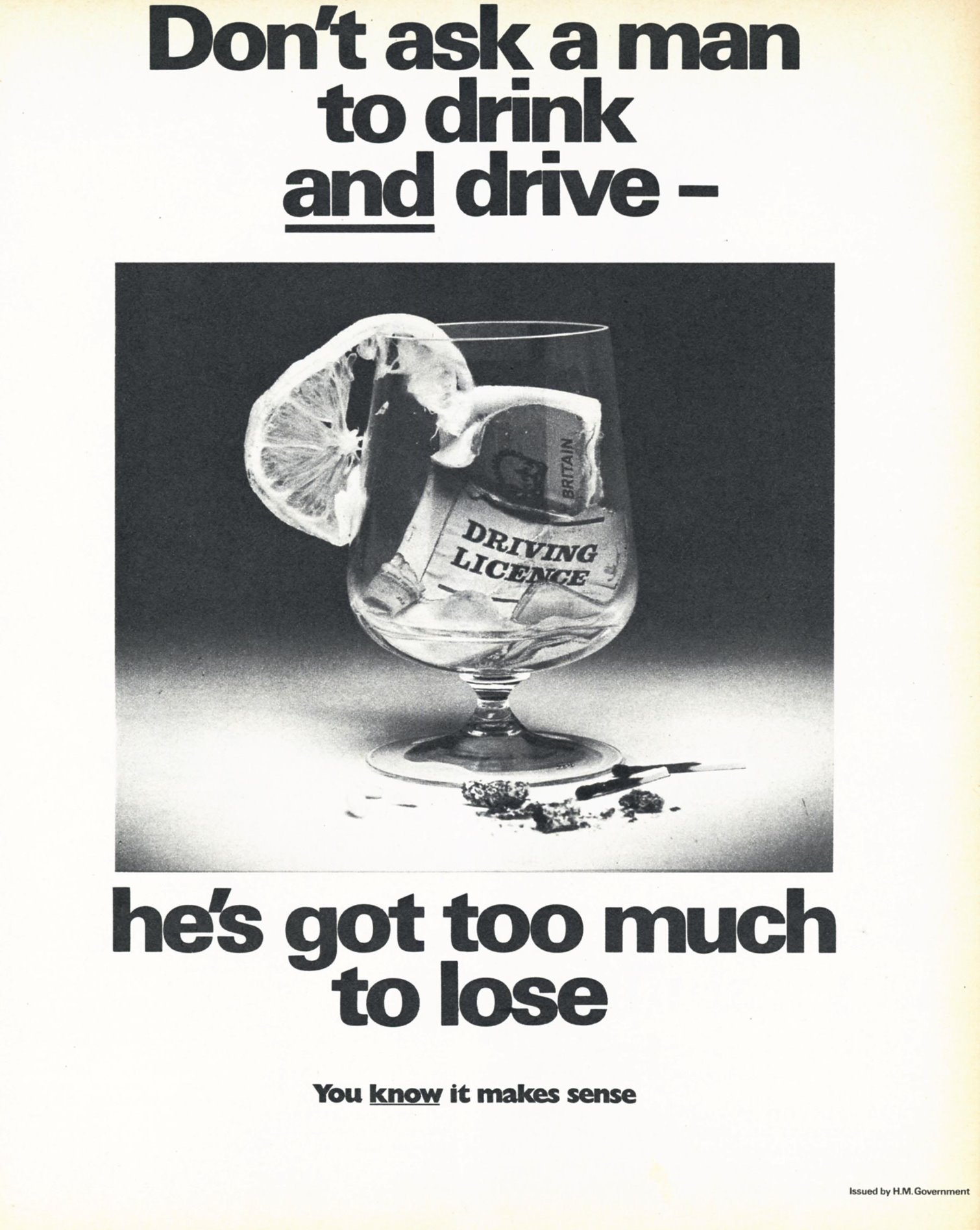

It was an offence to be drunk in charge of horses, carriages and trains back in Victorian times, and new-fangled motor vehicles inherited the same principles. But defining drink-driving was all rather subjective before a blood-alcohol limit was set by the Road Safety Act of 1967. The Department for Transport only began collecting statistics for drink-driving related deaths in the late 1970s, but it credits the Road Safety Act with making an important and continued impact in reducing the annual fatality count from 1,640 in 1979 to 220 in 2020.