I confess I have always had a soft spot for Marcia Williams as she was responsible for setting me on my own political journey. As Linda McDougall’s excellent biography explains, when Marcia first entered Downing Street she was taken aback by the old-school culture that existed – especially the practice of recruiting secretaries in Downing Street’s Garden Rooms solely from elite London secretarial colleges. She had it changed to a system of open competition from within the entire civil service secretarial pool and thus gave an opportunity to this young woman in 1976 to work behind the famous black door during Jim Callaghan’s premiership.

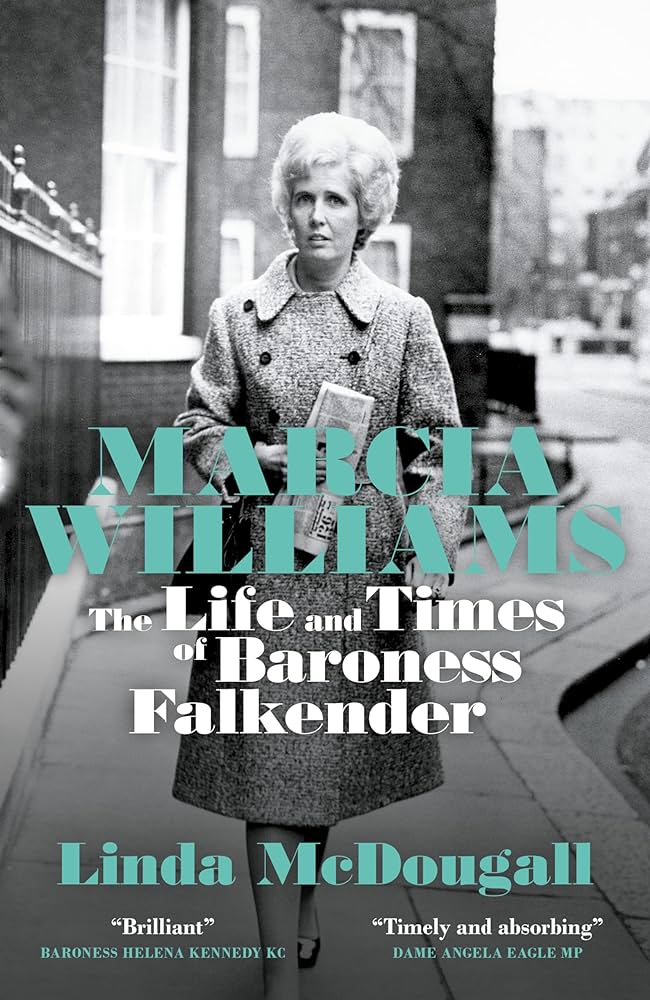

❱ The Life and Times of Baroness Falkender

❱ The Life and Times of Baroness Falkender

❱ Linda McDougall

❱ Biteback

So the story told in this book is of the distant past to many, but one for which I have sympathy and understanding. It is also why Marcia Williams – with her fair share of human failings – should be remembered as a trailblazer. It might have been the Swinging Sixties but the workplace, including the civil service, was still incredibly misogynistic. In 1964 only two senior civil service positions were held by women but on a different pay scale to their male colleagues, and women of executive rank were banned from the diplomatic service.

The radicalism of the 1945 government had been almost forgotten during the 13 years of Conservative government that followed. It was almost seen as an aberration from the natural order. When Labour won the election in 1964, prime minister Harold Wilson needed Marcia to continue the pivotal political role she had been playing that had won him the leadership and then the premiership. But there was no precedent for a political office in No.10, nor for a woman to lead it.

Coming into government after a long period in opposition is a paradigm shift for both politicians and civil servants and nothing prepares you for the relentless nature of being at the centre of government, whatever the era. Wilson needed the loyal eyes and ears of Marcia as well as her highly developed political brain and acumen.

McDougall describes herself as a storyteller and not a historian and there is quite a tale to be told of a woman who crossed the boundaries of what was normal for a woman of that time. She tells the story of a woman who lived and breathed politics and formed a partnership with Wilson that won four historic elections but never aspired to be in the front line herself. A woman who hid two pregnancies and in later years used prescriptions for uppers and downers to get her through the day. This book doesn’t shy away from Marcia Williams’ faults but it does chart the start of the enormous societal change that was beginning with the election of Labour in ’64 and which continues even now. In the ’80s, Labour women were still wearing badges proclaiming that “Labour Women Make Policy Not Tea”. So I am glad that Linda McDougall has written this book to explain The Life and Times of Baroness Falkender – and that I got to thank Marcia in person towards the end of her life for being a frontierswoman for those of us that followed.

Baroness Sue Nye is a Labour peer and former director of government relations for Gordon Brown