Steve Barclay, No.10’s new chief of staff, pledged on Sunday that the Johnson government would “step back” and favour “a smaller state”.

"Now, it is a priority to restore a smaller state – both financially and in taking a step back from people’s lives. It’s time to return to a more enabling approach. To trust the people, return power to communities, and free up business to deliver," Barclay wrote.

But how do we know what a “smaller” state is? Arguments over big versus small government often use different measures, and disputants talk past one another. So what measurements can we use?

I'd suggest four dimensions. The one that is exercising Conservative MPs most at the moment is government use of authority (laws, rules and regulations) because of Covid.

Government has indeed expanded its use of laws and rules into areas of activity few would have thought possible a couple of years ago. Partygate, as it is called, is happening because of laws about who could meet who and for what reasons during the pandemic.

More broadly, there has been a vast expansion of regulation in all developed countries over the past 100 years, and constant calls to "roll back" legislation. The Brexit wars were partly fought over regulation.

There is no simple way of measuring the amount of state regulation of individual or collective behaviour. We all know it’s gone up, but putting a number on it is tricky. And when people claim some governments make less use of regulation – Singapore, for example – they often ignore aspects of both formal and informal control those governments exercise.

Whilst the current government may be proclaiming its intention to shrink the regulatory power of the state in the economic sphere, and on public health, it is simultaneously increasing its regularity power of a number of civil liberties such as nationality, voting rights, protest, and restricting judicial review of its decisions.

Money is usually the other dimension people think about when they consider the size of government – specifically “getting and spending”. Government has certainly grown on this dimension, massively, during the pandemic.

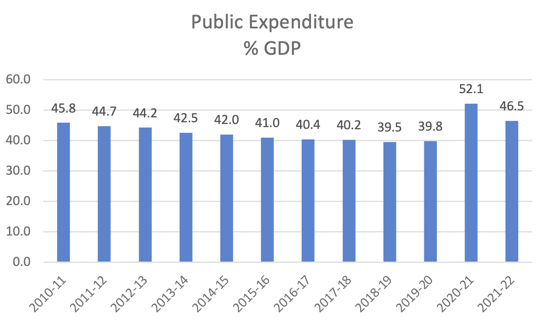

For the decade from 2010-11 to 2019-20, public expenditure in the UK steadily fell (relative to GDP). Then came the Covid pandemic.

The combination of large-scale expenditures on public health – such as the £37bn allocated to NHS Test and Trace and the massive almost-£70bn spent on the furlough scheme – and the economic impact of Covid restrictions massively increased public spending relative to GDP. Data for the below diagram comes from the Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis 2021.

Organisation is another dimension on which the size of the state can be measured. How much activity does the state directly organise? The most obvious measure of this is the level of public sector employment.

At the start of 2010, public sector employment stood at 22.3% of total employment. But by the start of 2019 – and the effects of a decade of austerity – ONS statistics show that had shrunk to just 16.5%.

This has to be treated with some caution, however. Over this period, some public sector jobs have been "outsourced" to private contractors – still paid for from public expenditure but now employed in the private sector. And some whole organisations have been reclassified as "private sector" – like much of further education.

The pandemic has also seen some largescale changes in this direction – new orgnaisations created to deal with the pandemic have largely been outside the public sector – such as test and trace, and the lighthouse laboratories that process Covid tests

However, the government has also promised increases in some areas of public employment – such as reversing the 21,000 cut in police numbers, expanding the number of NHS doctors and nurses, and so on. As a result there has been a slight uptick in public sector employment – up to 17.5% by the third quarter of 2021.

Information is the other – often neglected – dimension for measuring the size of government. Since the middle of the 19th century, developed countries have massively increased the state’s abilities to collect, analyse, and disseminate information about society – demographic, economic, social, health, and much more.

Control of such information can be a vital tool of government. A good example at the moment is the measurement of the Covid pandemic. This has been mainly a responsibility of government by the provision for testing and reporting infections both "on demand" (the free distribution of testing kits) and through a more accurate survey conducted by ONS.

One informational demand reportedly coming from the those like Steve Barclay who want a "small state" has been to end the free distribution of Covid test kits and, more controversially, to end the ONS survey. As then US President Donald Trump famously claimed in June 2020, "if we stop testing right now, we'd have very few cases, if any".

This neatly illustrates how the control of information flows can be a powerful lever for governments to shape public policy debate and – as we have seen during the pandemic – to influence public behaviour depending on the messages they put out (or don’t).

Authority, money, organisation and information are all powerful tools of government and dimensions for measuring – or at least estimating – the size of government. How far Steve Barclay and his colleagues will “roll back the state” on each of these remains to be seen.

Colin Talbot is emeritus professor of government at the University of Manchester and a research associate at the University of Cambridge